Section 10.2 Second Derivative Test

Why does the second derivative test work?

Recall that first derivatives tell you how to find the linear approximation to a function. For functions of two variables, we have

\begin{equation}

f(x+\Delta x,y+\Delta y) \approx

f(x,y) + \Partial{f}{x}\Delta x + \Partial{f}{y}\Delta y\tag{10.2.1}

\end{equation}

which we can also write as

\begin{equation}

\Delta f \approx \Partial{f}{x}\Delta x + \Partial{f}{y}\Delta y .\tag{10.2.2}

\end{equation}

At a local max/min, however, both partial derivatives vanish, and the linear approximation isn’t good enough to see what is happening. Instead, we need the quadratic approximation, which turns out to be

\begin{equation}

\Delta f \approx \Partial{f}{x}\Delta x + \Partial{f}{y}\Delta y

+ \frac{\partial^2f}{\partial x^2}(\Delta x)^2

+ 2\frac{\partial^2f}{\partial x\partial y}\Delta x\,\Delta y

+ \frac{\partial^2f}{\partial y^2}(\Delta y)^2 .\tag{10.2.3}

\end{equation}

At a local extremum, the first two terms vanish, and we are left with

\begin{equation}

\Delta f \approx

+ \frac{\partial^2f}{\partial x^2}(\Delta x)^2

+ 2\frac{\partial^2f}{\partial x\partial y}\Delta x\,\Delta y

+ \frac{\partial^2f}{\partial y^2}(\Delta y)^2\tag{10.2.4}

\end{equation}

So we need to understand the shape of a quadratic function of the form

\begin{equation}

h(x,y) = A x^2 + 2B xy + C y^2\tag{10.2.5}

\end{equation}

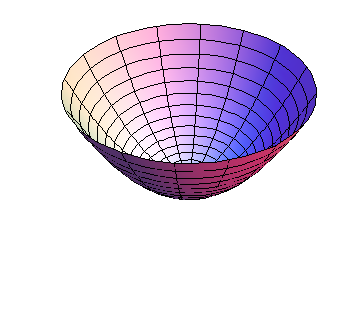

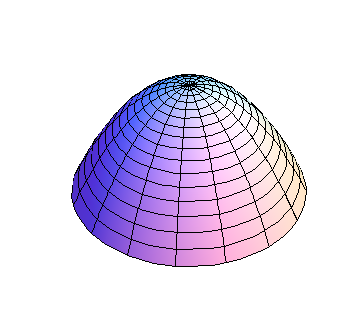

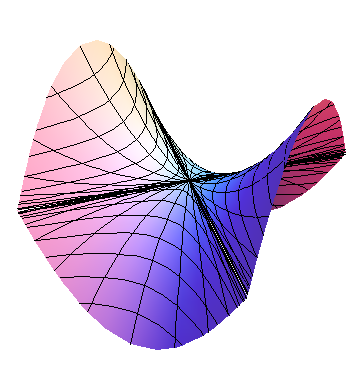

Consider first the simpler case when \(B=0\text{.}\) Then \(h\) is parabolic along both the \(x\) and \(y\) axes; the only question is whether the parabolas open up or down. If \(AC>0\text{,}\) both parabolas open in the same direction, and the graph is a paraboloid, as shown in Figures 10.2.2 and Figure 10.2.1, whereas if \(AC\lt 0\text{,}\) the graph is saddle-shaped, as shown in Figure 10.2.3.

For the general case, we need some algebra. Assume \(C\ne0\) and complete the square, yielding

\begin{align*}

A x^2 \amp+ 2B\,x\,y + C y^2\\

\amp=

C \left(y+\frac{B}{C}x\right)^2 + \left( A - \frac{B^2}{C} \right) x^2\\

\amp= C \left[\left(

y+\frac{B}{C}x\right)^2

+ \left( \frac{AC-B^2}{C^2} \right) x^2 \right]

\end{align*}

and set \(D=AC-B^2\text{.}\) Then if \(D>0\text{,}\) the term in square brackets is positive, and the graph of h is a paraboloid, which opens up if \(C>0\) (a min), and down if \(C\lt 0\) (a max), as shown in Figures 10.2.2 and Figure 10.2.1, respectively. If \(D\lt 0\text{,}\) then the term in square brackets is positive when \(x=0\text{,}\) but negative when \(y=-\frac{B}{C}x\text{;}\) this is a saddle, as shown in Figure 10.2.3. If \(C=0\) but \(A\ne0\text{,}\) a similar argument can be made replacing \(C\) by \(A\text{.}\) If \(A=0=C\) but \(B\ne0\text{,}\) then \(h=xy\text{,}\) which is easily seen to be a saddle. But if all of \(A\text{,}\) \(B\text{,}\) and \(C\) vanish, anything can happen; we need more information. Since \(D=0\) in this latter case, anything can happen if \(D=0\text{.}\)

Combining this argument with the form of \(\Delta f\) given in (10.2.4), we have

\begin{equation}

A = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2}

\qquad

B = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y}

\qquad

C = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2}\tag{10.2.6}

\end{equation}

and the argument given here reproduces the second derivative rule given in Section 10.1